🥁 Why Arrangement Starts With Drums

You've got a killer two-bar drum loop. The kick slaps, the snare cracks, the hi-hats groove perfectly. You could listen to it for hours.

But then what?

This is where most producers hit a wall. You know how to make beats, but turning those beats into complete songs feels like a completely different skill. You copy-paste your loop across eight minutes of timeline and wonder why it sounds boring. You add random sections hoping something will click. You lose the energy that made that original loop so exciting.

Here's the truth: your drums aren't just rhythm—they're the architectural blueprint for your entire arrangement.

Every great song, from trap bangers to festival anthems, builds its structure around the drums. The kick pattern determines where your drops hit. The snare placement defines your hook sections. The hi-hat variations create transitions and movement. Understanding how drums evolve from simple loops into complete arrangements is the difference between eight-bar ideas and finished tracks.

In this guide, I'm breaking down exactly how to take your drum patterns and turn them into professional arrangements that maintain energy, create anticipation, and guide listeners through a complete musical journey. No theory overload—just practical techniques you can use today.

What You'll Learn in This Guide

📜 A Brief History of Drum Patterns

Before we dive into modern arrangement techniques, let's understand where these concepts came from. Beat structure didn't appear out of nowhere—it evolved from decades of musical innovation.

The Foundation: Funk and Breakbeats

In the 1960s and 70s, funk drummers like Clyde Stubblefield (James Brown's drummer) created the syncopated, groove-heavy patterns that became the DNA of modern beat-making. That famous "Funky Drummer" break? It's been sampled thousands of times because it perfectly balances repetition with subtle variation—four bars that never get boring.

These drummers understood something crucial: rhythm is conversation. The kick and snare talk to each other. The hi-hats respond. Every hit has purpose beyond just keeping time.

The Revolution: Hip-Hop Sampling

When hip-hop pioneers started sampling these breaks in the 1980s, they discovered something magical. By looping a four-bar drum break and building music around it, they created hypnotic, head-nodding grooves. Producers like DJ Premier and Pete Rock turned repetition into an art form—the same loop for three minutes, but it WORKED because everything else evolved around it.

This loop-based approach fundamentally changed how we think about arrangement. Instead of drummers playing different patterns throughout a song, producers built entire tracks on variations of a single core groove.

The Expansion: Electronic Music and the Grid

The 1990s brought drum machines and DAWs, which introduced the grid—perfect timing quantized to mathematical precision. Genres like techno, house, and jungle took the loop concept further, creating driving, relentless patterns designed for the dance floor. Four-on-the-floor kicks. Breakbeat choppers. 808 sub patterns.

But here's what many forget: even the most repetitive techno track has arrangement. The drums might loop identically, but filters open, percussion layers in and out, and energy builds toward drops. The pattern stays constant while everything around it creates movement.

Today: Hybrid Approaches

Modern production blends all these traditions. Trap uses 808 patterns borrowed from hip-hop but arranged with EDM's build-and-release structure. Future bass combines pop's verse-chorus format with glitchy, evolving percussion. Drill takes UK garage's syncopation and applies trap's minimalist approach.

The lesson? There's no single "correct" way to structure drums. But understanding these traditions gives you a vocabulary to work with.

🎼 Basic Concepts: Rhythm, Bars, and Phrases

Let's establish the fundamental language of arrangement. If you've been producing for a while, some of this might be review—but stick with me, because understanding these concepts deeply changes how you build tracks.

Time Signatures and Bars

Most Western music uses 4/4 time—four beats per bar (or measure). When you count "1, 2, 3, 4" along with a song, you're counting one bar. Your DAW's grid shows these divisions clearly.

In electronic and hip-hop production, we typically work in multiples of four bars:

1 bar: Your basic drum pattern

2 bars: A phrase with call-and-response

4 bars: The minimum section length for most arrangements

8 bars: A complete musical phrase or section

16 bars: A full verse or chorus

Why these specific numbers? Because humans perceive rhythm in patterns of 2, 4, and 8. Our brains expect symmetry and resolution at these intervals. Breaking these expectations creates tension—which can be powerful when used intentionally.

The Loop Concept

A loop is simply a pattern that repeats. Your one-bar kick-snare pattern loops every four beats. But here's the key: effective loops balance repetition with subtle variation.

The best producers rarely loop anything identically for more than 8-16 bars without some change—even if it's just a hi-hat roll or a crash cymbal. The human ear craves both familiarity and novelty.

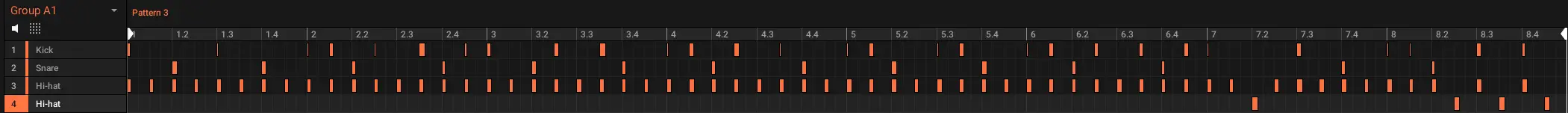

Static 1-bar loop

Varied 8-bar phrase

Rhythmic Density and Space

Not every bar needs to be packed with hits. Space is rhythm too. Notice how trap often uses sparse, minimal drums—just kick, snare, and hi-hats with plenty of room between. That emptiness creates weight and impact when the hits do land.

Contrast this with drum and bass, where rapid hi-hats and intricate percussion fill almost every sixteenth note. Same grid, completely different energy.

Understanding how dense or sparse to make your patterns is fundamental to arrangement. Verses might use minimal drums to let vocals breathe. Choruses might add layers for energy. Breakdowns might strip to just kick and sub.

🔨 Common Beat Structures

Let's break down the fundamental relationships that make drum patterns groove.

The Kick-Snare Relationship

In 4/4 time, the most basic pattern is:

Kick: Beats 1 and 3

Snare: Beats 2 and 4

This is your rock-solid foundation. The kick provides forward momentum. The snare provides the backbeat—that satisfying crack that makes you want to clap or nod your head.

But here's where it gets interesting. Variations on this basic pattern define entire genres:

Hip-Hop: Often keeps kick on 1 and 3, but adds an extra kick right before beat 2 or 4 for bounce

Trap: Doubles or triples the kick rolls, creating rapid fire "kick-kick-kick-snare" patterns

House: Four-on-the-floor kicks (every quarter note), with snares or claps on 2 and 4

Breakbeat: Syncopated kicks that DON'T always land on the downbeat, creating swing and surprise

Groove and Swing

Perfect quantization sounds robotic. Real groove comes from subtle timing variations called swing or shuffle.

In your DAW, swing typically delays every second hi-hat hit by a tiny amount (usually 8-15%). This creates the "drunk" or "bouncy" feeling in hip-hop and trap.

💡 Pro Tip: Don't apply swing to everything. Usually just the hi-hats need it. Keep kicks and snares quantized for punch, add swing to hats for groove.

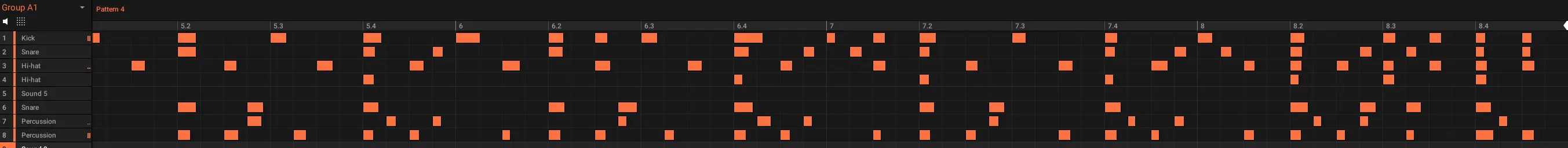

Layering Percussion for Movement

Once you have your kick-snare foundation, percussion creates variation and interest:

Hi-hats: Define the groove's speed and feel (eighth notes = hip-hop feel, sixteenth notes = trap/EDM feel)

Open hats: Accent specific beats (usually beat 4) for emphasis and transition signals

Shakers and tambourines: Fill space between hi-hats, adding texture without changing the core rhythm

Claps and snaps: Double or replace snares for emphasis in chorus sections

The key is layering elements gradually. Start minimal. Add one element every 4-8 bars. By the time you reach your chorus or drop, you've built up to maximum percussion density without overwhelming the listener.

🎯 From Beat to Section

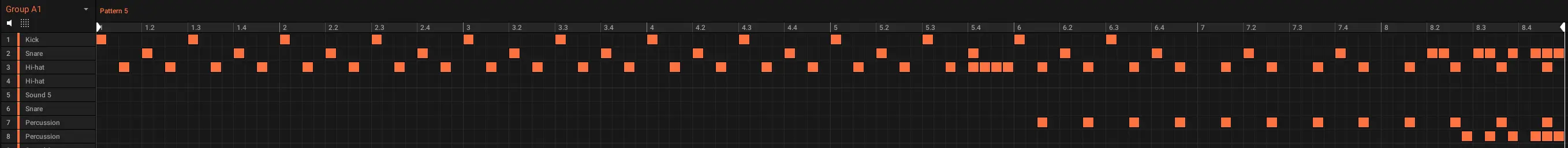

You've got a solid one-bar drum loop. Now let's turn it into an eight-bar section that actually moves somewhere.

Step 1: Duplicate and Establish (Bars 1-4)

Copy your one-bar loop across four bars. Don't change anything yet—just let it establish the groove. Four bars gives listeners time to lock into the rhythm before you introduce variation.

Step 2: Add Variation (Bars 5-7)

Now introduce subtle changes:

Bar 5: Add a hi-hat roll leading into bar 6

Bar 6: Same as bars 1-4, but add an extra percussion layer (shaker, tambourine)

Bar 7: Remove the kick on beat 3 to create anticipation

These micro-variations maintain the core groove while preventing listener fatigue.

Step 3: Signal Transition (Bar 8)

Bar 8 is your transition bar. This is where you signal that something new is coming:

- Snare rolls increasing in speed

- Riser sound effects

- Remove the kick entirely (just snare and hats)

- Crash cymbal on beat 1 of the next section

This eight-bar structure—establish, vary, transition—is the foundation of all arrangement. Whether you're building an intro, verse, or drop, this pattern keeps things moving forward.

💡 Pro Tip: Duplicate your drum loop but mute the kick every 4th bar to add variation. This creates breathing room and makes the kick's return more impactful.

📊 Song Arrangement Basics

Now that you understand eight-bar sections, let's zoom out to full song structure.

Typical Song Structures

Most songs follow predictable forms because these patterns work—they guide listener attention and create satisfying journeys:

Simple Loop Format (Hip-Hop/Lo-Fi):

Intro (8 bars) → Verse (16 bars) → Verse (16 bars) → Bridge (8 bars) → Outro (8 bars)

Verse-Chorus Format (Pop/Rock):

Intro (8) → Verse 1 (16) → Chorus (8) → Verse 2 (16) → Chorus (8) → Bridge (8) → Chorus (8) → Outro (8)

Build-Drop Format (EDM):

Intro (16) → Buildup (16) → Drop (16) → Breakdown (16) → Buildup (16) → Drop (16) → Outro (8)

Notice the common thread? Sections are multiples of 8 bars, and patterns repeat with variation. Listeners need repetition to latch onto ideas, but they need variation to stay engaged.

Energy Curves and Dynamic Flow

Think of your arrangement as an energy rollercoaster. You can't maintain peak intensity for an entire track—listeners will tune out. Instead, create waves of tension and release:

Low Energy: Minimal drums (just kick and snare), open space, fewer elements

Medium Energy: Full drum kit active, melodies present, steady forward motion

High Energy: Maximum percussion layers, driving rhythm, all elements playing

A typical energy curve might look like:

Intro (Low) → Verse (Medium) → Chorus (High) → Verse (Medium) → Chorus (High) → Bridge (Low) → Final Chorus (Highest) → Outro (Low)

The drums are your primary tool for controlling this energy. More drum layers = more energy. Fewer layers = more space and anticipation.

The Power of Contrast

The best arrangements use contrast to make sections distinct:

Sparse verse drums make the full chorus drums hit harder

Removing drums entirely in a breakdown makes their return feel massive

Stripping to just kick and bass creates tension before everything drops back in

Don't be afraid of silence or near-silence. Some of the most powerful moments in music happen when drums cut out completely.

🎸 Genre Examples

Let's apply these concepts to specific genres and see how drum arrangement creates different vibes.

Hip-Hop (Loop-Driven)

Hip-hop often uses the same core drum loop throughout, with minimal variation. The drums establish a pocket, and everything else—vocals, samples, bass—does the heavy lifting for arrangement.

Typical Structure:

- Intro (8 bars): Just drums, maybe filtered or with reverb

- Verse 1 (16 bars): Full drums + bass, minimal melody to let vocals shine

- Hook (8 bars): Add melodic elements, maybe double snare hits

- Verse 2 (16 bars): Same as Verse 1, maybe add subtle percussion layer

- Hook (8 bars): Exactly like first hook (repetition is key)

- Bridge (8 bars): Drop drums briefly, or switch to half-time feel

- Outro (8 bars): Drums gradually filter out or fade

Key Technique: The drums barely change, but automation on filters, reverb, and volume creates movement. A low-pass filter opening during the hook makes it feel like it's lifting without changing the beat.

EDM (Drop-Based)

EDM arrangement is all about tension and release. Everything builds toward "the drop"—that moment when full drums and bass hit after a buildup.

Typical Structure:

- Intro (16 bars): Minimal drums (just kick, or kick + hi-hats), establishing groove

- Buildup 1 (16 bars): Gradually add percussion layers every 4 bars, increase hi-hat speed, add risers and drum fills in final 8 bars

- Drop 1 (16 bars): FULL DRUMS—four-on-the-floor kick, snare on 2 and 4, rapid hi-hats, all percussion layers active

- Breakdown (16 bars): Strip to minimal drums or just melodic elements, give listeners a breather

- Buildup 2 (16 bars): Same structure as first buildup but with variations

- Drop 2 (16 bars): Same as Drop 1 but add extra percussion or change hi-hat pattern for variation

- Outro (8 bars): Gradually remove drum layers, fade out

Key Technique: The buildup is everything. Start with just kick. Every 4 bars, add another layer: clap on 2 and 4, then hi-hats, then shakers, then full percussion. The last 8 bars before the drop should have drum rolls and risers increasing in intensity. The drop's impact depends entirely on how well you build anticipation.

Pop (Verse-Chorus)

Pop uses clear verse-chorus dynamics. Verses are spacious to feature vocals. Choruses are full and energetic to create memorable hooks.

Typical Structure:

- Intro (8 bars): Sparse drums or rhythmic elements that hint at main pattern

- Verse 1 (16 bars): Kick and snare only, or kick + minimal hi-hats—let vocals be the focus

- Pre-Chorus (8 bars): Start adding hi-hat layers and percussion, building energy

- Chorus (8 bars): Full drum kit—kick, snare, hi-hats, claps, shakers, everything working together

- Verse 2 (16 bars): Back to verse arrangement, maybe with subtle additions from chorus

- Pre-Chorus (8 bars): Same buildup

- Chorus (8 bars): Identical to first chorus

- Bridge (8 bars): Different drum pattern entirely—half-time, double-time, or stripped back

- Final Chorus (8-16 bars): Biggest version—double snares, add extra claps, maximum energy

- Outro (8 bars): Gradual removal of elements

Key Technique: The contrast between verse and chorus is dramatic. Verses might have just kick and snare, while choruses have 6-8 percussion layers. This dynamic range makes the chorus feel huge without actually changing volume much—you're changing density instead.

🚀 Producer Tips: Keep It Interesting

You know the structures. You understand energy curves. Now here are the advanced techniques that separate good arrangements from great ones.

1. Automation Is Your Secret Weapon

Don't just turn elements on and off—automate their characteristics:

- Hi-hat volume: Gradually increase throughout a section for natural buildup

- Snare reverb: Automate reverb send from 0% to 50% across 8 bars for lifting effect

- Kick filter: Low-pass filter your kick during verses, open it for chorus impact

- Percussion panning: Automate shakers or tambourines to move across stereo field

These subtle changes keep arrangements dynamic without requiring new MIDI patterns.

2. The Dropout Technique

Strategically remove elements to create tension:

Bar 8 of any section: Drop all drums except snare for one bar before transitioning

Final beat of a buildup: Silence everything for one beat, then drop hits HARD

Pre-chorus: Remove kick for 2-4 bars while keeping snare and hats—creates lift

Silence creates anticipation. Use it liberally.

3. Variation Through Rhythm, Not Sound

Instead of adding new drum sounds, change the rhythm of existing ones:

- First chorus: Standard hi-hat pattern

- Second chorus: Same hi-hat sound but double-time (twice as fast)

- Third chorus: Triplet feel for different groove

This creates variation while maintaining sonic consistency.

4. Ghost Notes and Grace Notes

Professional arrangements use extremely quiet hits (ghost notes) between main hits to add subtle groove. These barely-audible snare or hi-hat hits at 20-30% velocity make patterns feel more human and less rigid.

Try adding ghost snares between your main snares. You'll barely hear them in the mix, but they make the groove feel more alive.

5. Transitional Elements

The difference between amateur and pro arrangements often comes down to transitions. Use these to connect sections smoothly:

Drum fills: Two bars before section changes

Risers: Synth or noise sweeps during final 8 bars of buildups

Impacts: One-shot crash/boom on downbeat of new section

Reverses: Reversed crash or snare leading into section changes

Never let sections just START—always signal what's coming.

💡 Pro Tip: Create a "transitions" track in your project. Whenever you need a fill, riser, or impact, you know exactly where to look. This speeds up arrangement workflow dramatically.

🎨 Arrangement Is Storytelling Through Rhythm

Here's what took me years to understand: arrangement isn't about following rules. It's about guiding listeners through an experience.

Your intro sets the scene. Your verses create context. Your choruses deliver the emotional peak. Your bridge provides perspective. Your outro offers resolution.

The drums aren't just keeping time—they're the narrator of this story. They tell listeners when to pay attention, when to relax, when to expect something big, and when to settle down.

The producers you admire—Metro Boomin, Flume, Calvin Harris, Mike Dean—they're all master storytellers. They understand that repetition creates familiarity, variation maintains interest, and contrast creates impact. Their arrangements feel inevitable, like they couldn't have been structured any other way.

But here's the secret: they got there through experimentation. They tried structures that didn't work. They made transitions that fell flat. They built drops that were anticlimactic. And they learned from every mistake.

So stop overthinking. Open your DAW. Take that drum loop you've been working on and start building sections around it. Try a verse arrangement. Experiment with a drop. Test different transition techniques.

Some arrangements will fail. Some will feel forced. But some—SOME—will surprise you with how naturally they flow. Those are the arrangements you'll build on, develop your style from, and eventually use to define your sound.

Arrangement is where production becomes art. Where technical skills transform into creative expression. Where your beats become songs.

Your drums are ready. Now give them a story to tell.

Stay sharp. Stay structured.

— ToneSharp